1997-Present

“This willingness to reject conventional ideas about electronics, music, and electronic music defines Octant’s unpretentious yet inventive stance.”

– Heather Phares (AllMusic)

“…a stunning burst of new wave pop hooks and primitive electronica that actually works against all odds.”

Alternative Press (12/99)

Octant Background Notes

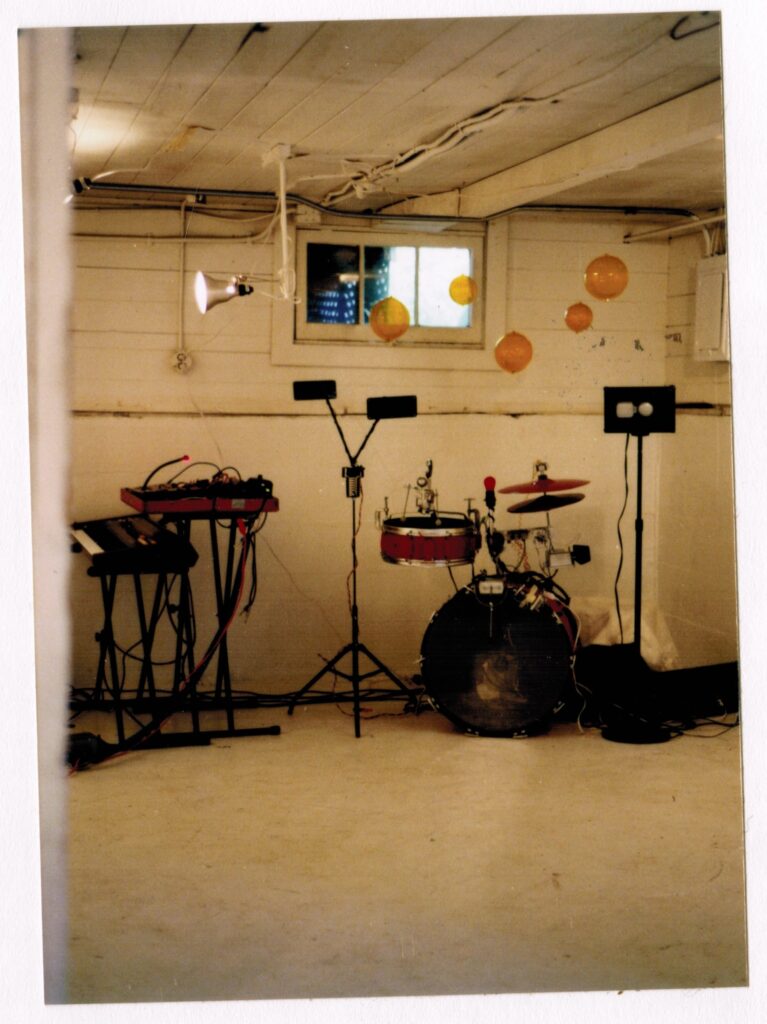

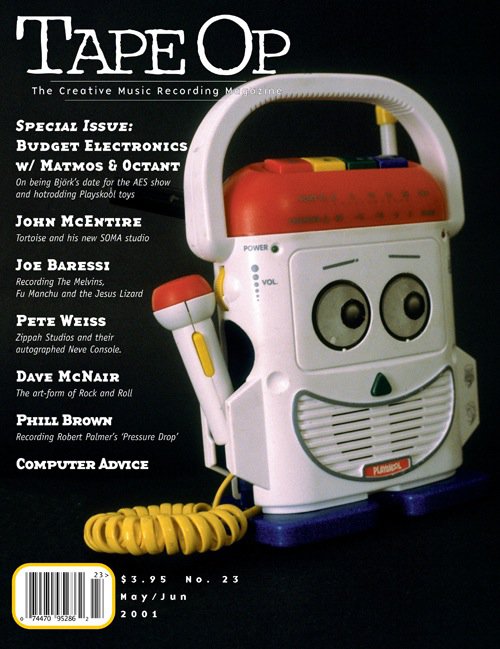

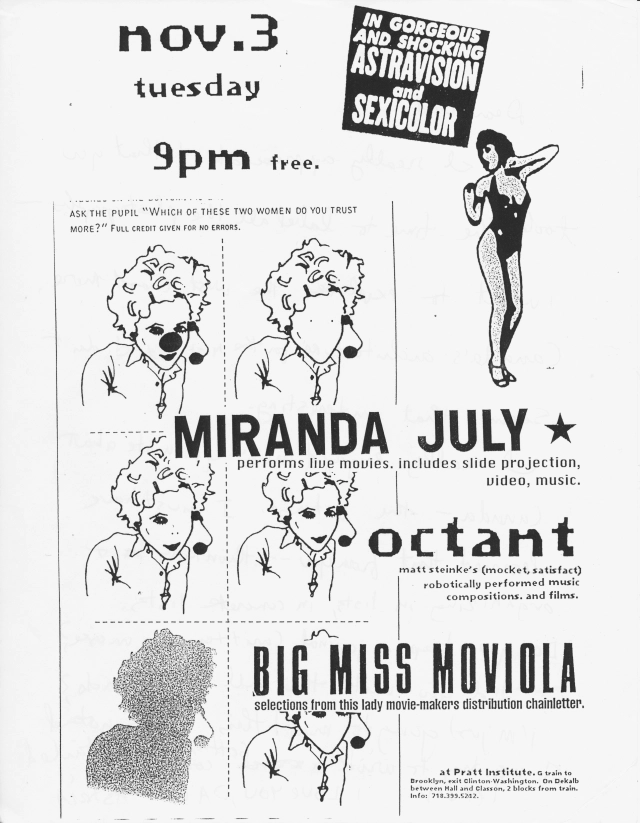

Octant became a multimedia experience where machine-human interactions, kinetic art, lighting, and music converged in everyday bars and all-ages venues. While robotic percussion could have been regarded as a cheap gimmick, my focus was on creating compelling sounds and visually engaging instruments. Looking back, Octant was ahead of its time, foreshadowing the rise of homemade instruments in electronic music and the Maker movement that gained traction a decade later. Octant was also embedded within the DIY post-punk scene of the 1990s Northwest, joining the creative ranks of bands on labels like K, Kill Rockstars, and Up Records, as well as other DIY projects like Miranda July’s Joanie 4 Jackie (formerly Big Miss Moviola).

Using a robotic percussionist began as a dare from a bandmate in another project, as drummers were hard to find and often over-committed. Developing an acoustic drum machine addressed a technical problem while offering an intriguing aesthetic experiment. I aimed to create a touring and recording project that operated like a conventional band while learning to program music, design circuits, and craft new musical objects. This process sparked a deep and ongoing exploration into robotics and experimental instruments within art.

1999 Album, “Shock-No-Par”

The Octant album Shock-No-Par, released in 1999, serves as a significant milestone in incorporating robotic musical instruments into live performances. The project integrated traditional, experimental, and robotic instruments, merging indie rock with experimental textures. The release contributed to the discourse on robotic musicianship, illustrating its capacity to expand the role of the composer to include performer, producer, instrument designer, and sculptor.

More reviews are below.

A documentary that was shot in 1999 in conjunction with the release of the first record, Shock-No-Par.

Machine Project, LA 2011